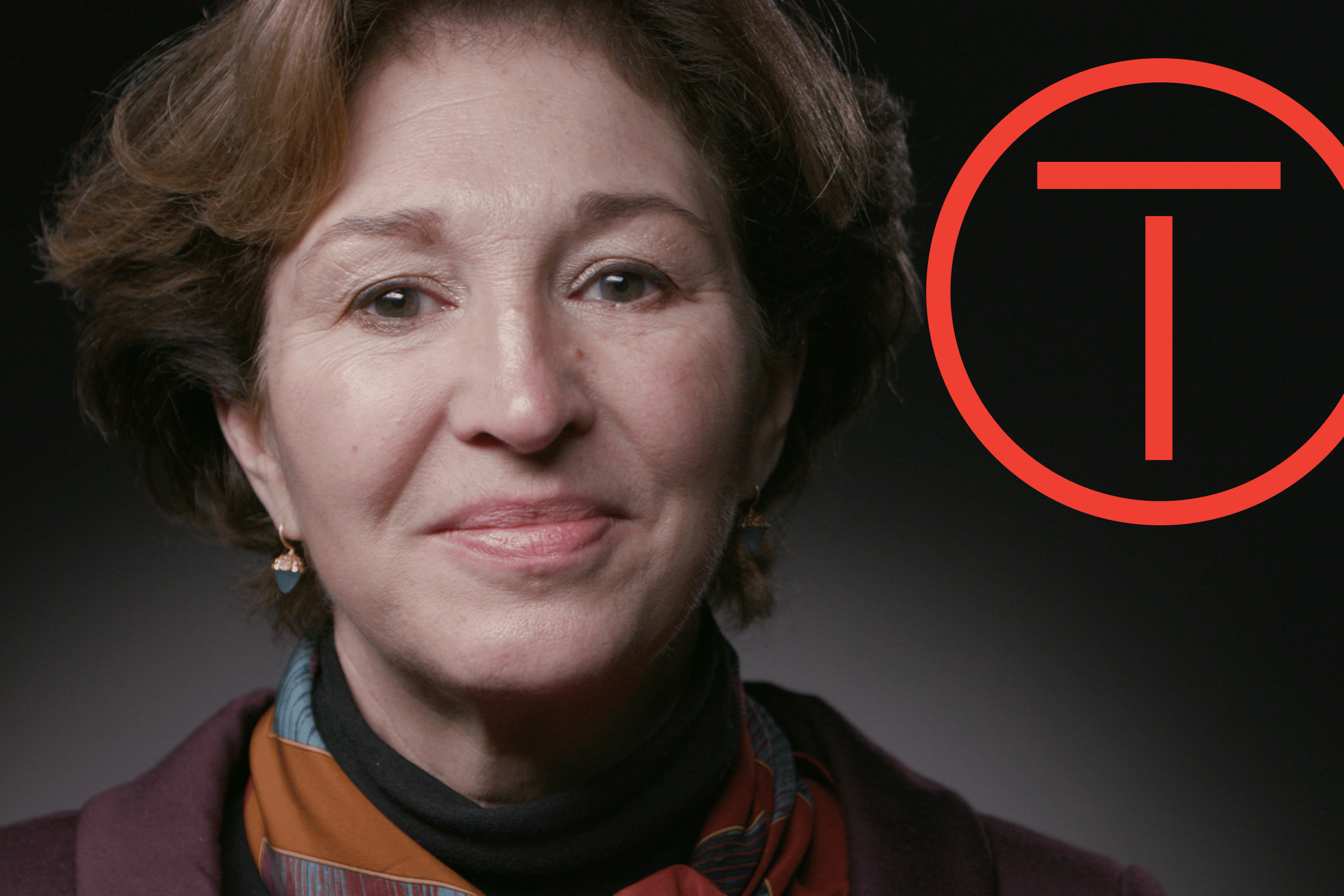

When I first met Anne-Marie Slaughter, it felt like encountering a celebrity. This was 2013, a year after she published an article in the Atlantic – Why Women Still Can’t Have it All – which had gone viral. It described the challenges she faced trying to balance work and family as the Director of Policy Planning for then-Secretary of State Hilary Clinton, and her epiphany about the stalled gender equality movement. Like many people, I’d devoured the article, pondering what it meant for my own life and career trajectory.

And then came the announcement: She was going to become the new president at New America, the nonpartisan think tank where I worked.

During her first visit to the New America office, she surprised me by walking up to my cubicle – I was just a lowly junior staffer! – peppering me with questions, and seeming to genuinely care about my opinions. Over the next few years, she would become one of my mentors, nurturing my ambition and proving to be an inspiring example of leadership.

This was true even in times of crisis – like the one she faced in 2017 when an employee publicly accused her of firing him and his colleagues because of funder pressure. It challenged what she knew about leadership and changed her forever.

What spurred those changes? Part of it was the situation, and part of it was the people who surrounded her afterwards: a coach, trusted colleagues and board members – people who encouraged her to lean into the criticism and become a more receptive leader.

Her new book about the lessons of that 2017 crisis is called Renewal. As part of the Torch Lead By the Book leadership conversation series, I sat down with her to talk about what it means to lead from the edge and the center, the “constant unfolding” of leadership, and what we can learn from tracking our questions. Our edited conversation is below.

In your book, you write about starting to work with your leadership coach. Through that relationship, you had a revelation: despite lecturing and writing about forms of more participatory, horizontal leadership, you were not practicing what you had been preaching. You were telling others that “power and leadership could be about connection as much as control,” encouraging leaders to lead from the center of a web rather than from the top of a ladder, arguing that networks could be transformative for problem solving and governance. Could you talk about what you learned, and how your leadership style has evolved?

One of the themes that I emphasized in the whole idea of renewal is being able to look in the mirror and see yourself the way others see you. I thought of myself as a horizontal leader – in other words, somebody who minimized hierarchy and was inclusive. In fact, that’s not how many others at New America experienced my leadership. I was not letting myself be in a situation where I was listening as much as I was talking, where I was hearing not just what other people felt, but what they thought about where we might be able to go .

I’ve now come to think about leading more like a process of flattening the hierarchy where you can and recognizing that sometimes it will need to pop back up. It’s almost like taking an accordion and turning it on its side. So sometimes it’s up, and then sometimes you can flatten it.

Even when you have those participatory, less hierarchical spaces, you have to make a very deliberate effort to hear from those that are on the edge . People at the edge of the web are also at the bottom of the ladder. They are the people who often feel like they have the least power or the least connection. I’m not going to say I’ve mastered this, but at least I understand how to think about it and how to try to create settings in which that can work.

If someone who reads this and says, I want to try this strategy of leading more from the center and the edge, where does this person start?

One step is to hold office hours, which I do regularly. Anyone can sign up. More formally, I have found that sharing power with someone who does not look like me has made a huge difference. The last thing is very deliberately to structure processes where you have managers and staff all on an equal plane. For us, that’s been our equity process, where with the guidance of a spectacular consultant, we’ve had equity trainings that are not your usual trainings. Staff break into groups of four or five, and you just have no idea who is going to be in that group – directors, junior policy analysts, people from central services. Everyone is learning together in a way that is much more equal.

Much of your book articulates your evolution of becoming a more receptive leader – accepting feedback and opinions from others and valuing their perspectives as you work towards your own personal growth. As you describe, this can be challenging and uncomfortable. We’re wired to defend our personal choices as being smart or right. But I’m curious if you could talk about the flip side of this evolution: what has been the most rewarding part of becoming more receptive?

The advice I got from a board member when New America was in crisis was, “run towards the criticism.” And I think about it still when I’m feeling defensive. I remind myself, ‘lean toward it, ask for it. Find ways to make it easy for people to tell you what they think.’

In those situations, I often use the technique of self-deprecating humor. So if I suspect that the people around me are thinking, ‘Oh, God, here she goes again,’ I’ll voice that: ‘So I’m sure you all are thinking X.’ And they may not be exactly thinking X. But it gives them the freedom to tell me more of what they’re really thinking. Honestly, I don’t know how you can lead if people aren’t telling you what they’re really thinking.

I’m not suggesting we define ourselves only in the eyes of others. But I am saying all of us know that we’ve got things we’ve got to work on. And where you feel the most defensive, that’s a good guide . I think you feel stronger and better rather than putting barricades up against something you know inside is right.

It sounds like there’s a sense of freedom that comes from letting go of the defensiveness and being able to take yourself a little less seriously, to laugh at yourself.

Yes, that is absolutely right. Some of the very best leaders I know are wonderfully self-deprecating in a way that does not undermine their gravitas. And I know a lot of people worry, particularly if you’re a woman, that you have to maintain a certain gravitas. But I think you can project confidence with the very ability to laugh at yourself.

I love the part of the book where you encourage people to track the questions that they keep asking, across every relationship or every job. What can we learn from that kind of question tracking? What have you learned from it?

I got that from John Gardner, who’s also written about renewal. He says the hostile person keeps asking ‘why are other people so unpleasant?’ If you keep asking, ‘Why won’t this person just agree with me?’ Or ‘why are people so unpleasant?’ and you find you’re asking this across multiple interactions, that’s telling you something about you, not about them.

I tend to be very high energy, and I want to do all sorts of things. And I love to transform places. As I moved from job to job, I found myself asking, ‘why aren’t other people as enthusiastic about changes as I am? Why don’t they see this great vision?’ Over time, I realized it wasn’t that people weren’t excited about change, it was that I was overloading them. One of my deficits is I don’t think through all the steps that are going to take to realize something. But if you’re somebody who’s trying to implement what you think I want, and I’m giving you the fourth idea of the month, you get burned out, you get exhausted.

It’s essentially spotting patterns. As you begin to identify your own reaction to other situations, you can start to realize, maybe it’s me.

You write in the book that, “leadership can be a continuous process of learning and exploration.” What is the latest thing you’ve learned from that process of exploration?

I was talking to my husband and son the other day about a great conductor. On his deathbed, he said, “I think now I know a little something about Mozart.”

I thought, that’s exactly it. It is a constant unfolding. And part of that is you yourself aging, but also accreting experience and processing later experience in light of earlier experience. There’s always more to learn. I’m over 60 and I’m learning to lead collaboratively. When I started leading, it was much more important for me to project confidence, to be more in that masculine kind of image of what leadership is. It’s also because I was a younger woman, and I’m now older.

It’s a constant process of learning. If you’re not continuing to learn and grow, then it’s time to find something else to do.